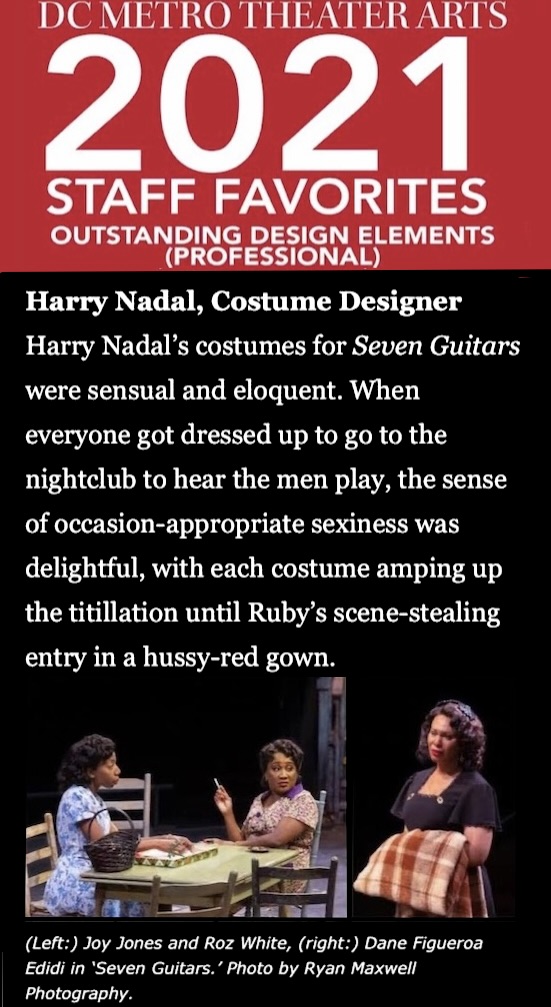

Conductor Lidiya Yankovskaya and soprano Alicia Russell at a concert performance of Freedom Ride at MassOpera, in November 2019 © Maggie Hall

Freedom Cry

A new opera about a seminal moment in U.S. history opens this month at Chicago Opera Theater.

By Katherine Dubbs

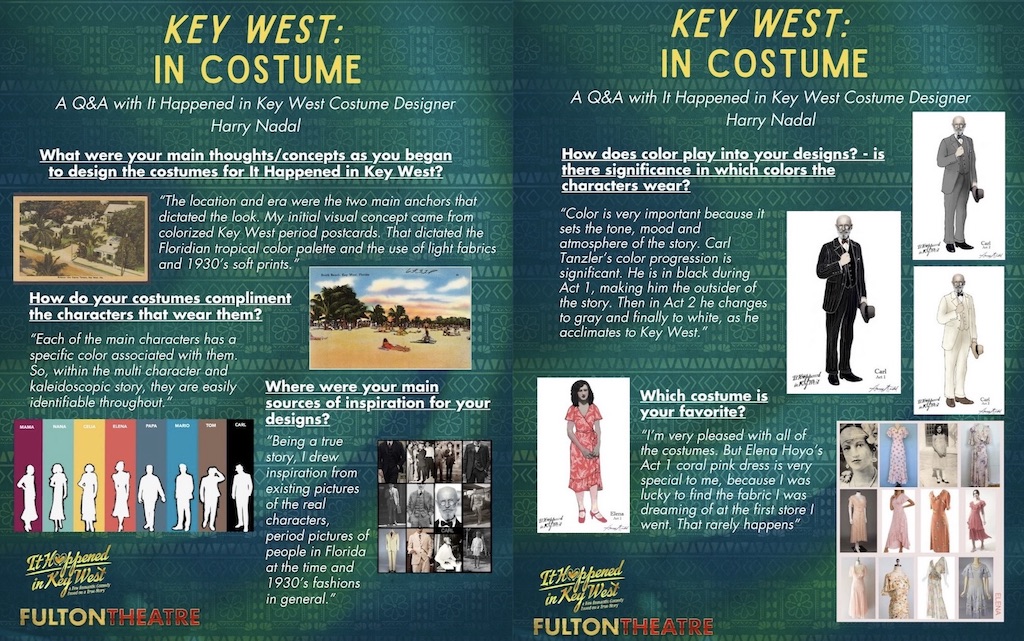

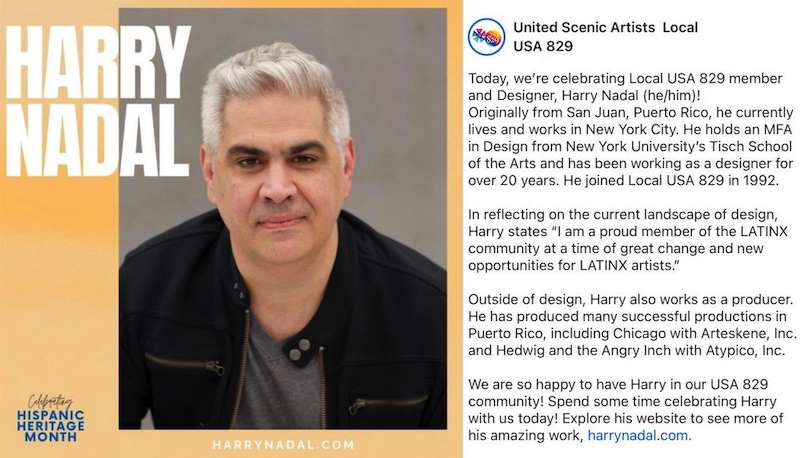

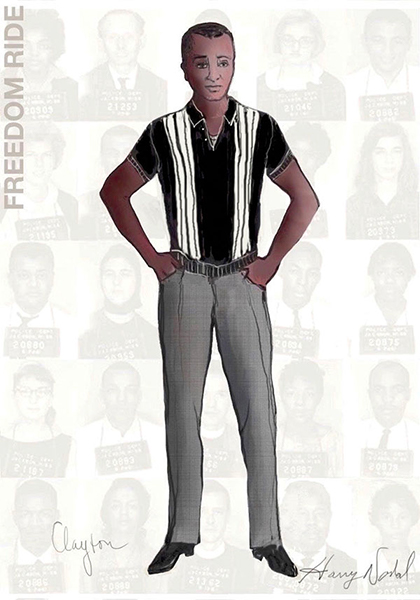

Costume Design by Harry Nadal

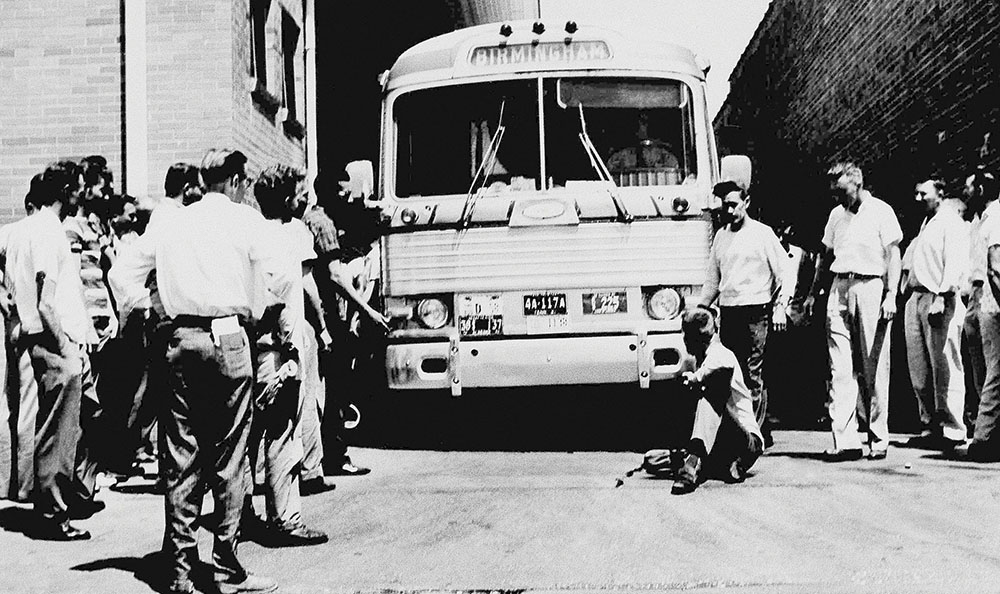

ON FEBRUARY 8, Chicago Opera Theater presents the world premiere of Dan Shore’s Freedom Ride, the story of a black university student who decides to take an active role in the U.S. civil-rights movement as a “Freedom Rider.” In May 1961, the Congress of Racicivil rights organization, selected seven black interstate bus line from Washington, D.C., to New Orleans. Although segregation in bus seating had been ruled unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court as early as the mid 1940s, the rulings were not enforced in the South, and buses remained segregated. During the summer and early fall of 1961, more buses carried young activists from across the U.S. into the Deep South to defy segregationist practices; the so-called “Freedom Riders” were trained in CORE’s tradition of nonviolent civil disobedience. The Freedom Riders were arrested by local and state police, and many were turned over to angry mobs and beaten.

Costume Design by Harry Nadal

The work of the Freedom Riders ultimately led to the enforcement of federal policies intended to dismantle the legacy of Jim Crow segregation on bus lines and in bus terminals in the South. The Freedom Riders inspired other activists during the civil-rights movement, and composer Shore, who also crafted the libretto for Freedom Ride, believes that the work of the Freedom Riders remains inspirational today. “I would love for younger audience members to see [Freedom Ride] and say, ‘Wait a minute—this was a movement by young people who thought there was nothing they could do, but they found something they could do, and what they did was ultimately successful,’” he says.

Shore began working on the opera while teaching at Xavier University of Louisiana, a historically black college in New Orleans. “Freedom Ride was created and workshopped in very close collaboration with my colleagues at Xavier, several of whom lived through these events themselves, and my students at Xavier, who were every day living out the challenges of being a young African–American in the South,” Shore says. He acknowledges that as a white man he has a different perspective on the civil-rights movement from that of Sylvie Davenport, the fictional African–American protagonist of Freedom Ride. “All I can do is recognize the fact that I’ve been extremely privileged to tell this story and to do everything I can to get as much input as I possibly can from everyone around me to make sure that the work itself rings true for people.”

COT music director Lidiya Yankovskaya, who conducts the Freedom Ride run, is enthusiastic about how the opera fits the company’s commitment to diversity and its development of new American opera. “In opera today, and in opera in general, there’s a shortage of powerful female characters who are not abused in some way,” Yankovskaya says. “In Freedom Ride, we have Sylvie, a strong, educated black woman who decides over the course of the opera to take a risk, to take a stand, to stand up for what she believes in. She’s an extremely powerful character that we can not only relate to but also use as a model for our own lives.”

Freedom Rider bus in Alabama, May 1961 Associated Press

Baritone Robert Sims, who sings the role of Clayton Thomas in Freedom Ride, has a particularly strong connection to the subject matter. “The idea of walking onto a Freedom Ride bus is like the final scene in the Dialogues of the Carmelites, when the nuns are singing ‘Salve Regina’ and walking to the guillotine,” he says. “Walking onto that bus was inviting death.” The baritone stresses the contemporary resonance of the new opera. “What I want people to realize when they look at Freedom Ride is that although it was only fifty-plus years ago, on some level in our political climate now, things haven’t really changed…. Some of those people that beat and killed those youths are still alive today. And have their hearts and minds changed?”

Much of Shore’s score is inspired by the music the Freedom Riders sang during their journeys, as well as by the rich musical tradition of Louisiana, including blues, gospel and African–American spirituals. Stage director Tazewell Thompson says the spirituals are “an oral history depicting the hardships of slavery. They are songs of protest and solace. Spirituals’ influences belong in a work about racial disharmony and civil-rights strife in America.”

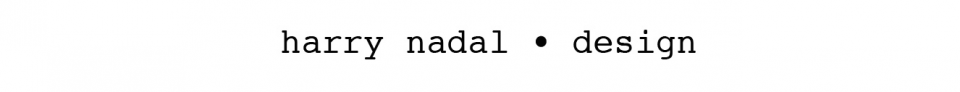

The set and costume designs, period-specific but minimalistic, feature a monochromatic palette to reflect the racial tensions of the early 1960s and to echo the black-and-white archival pictures that are projected in the production. “This design choice is a grand operatic gesture to emphasize the period and the power of the story and the music,” says costume designer Harry Nadal.

Freedom Ride asks audiences to think critically about their role in today’s increasingly multicultural society, and to consider whether we truly promote liberty and justice for all. “The opera puts it out there for you to decide,” Sims says. “Where do you stand? What do you believe? Do you believe in civil liberties for everyone? Or just a chosen few?”

Katherine Dubbs is an opera director, arts entrepreneur and graduate student at MIT.